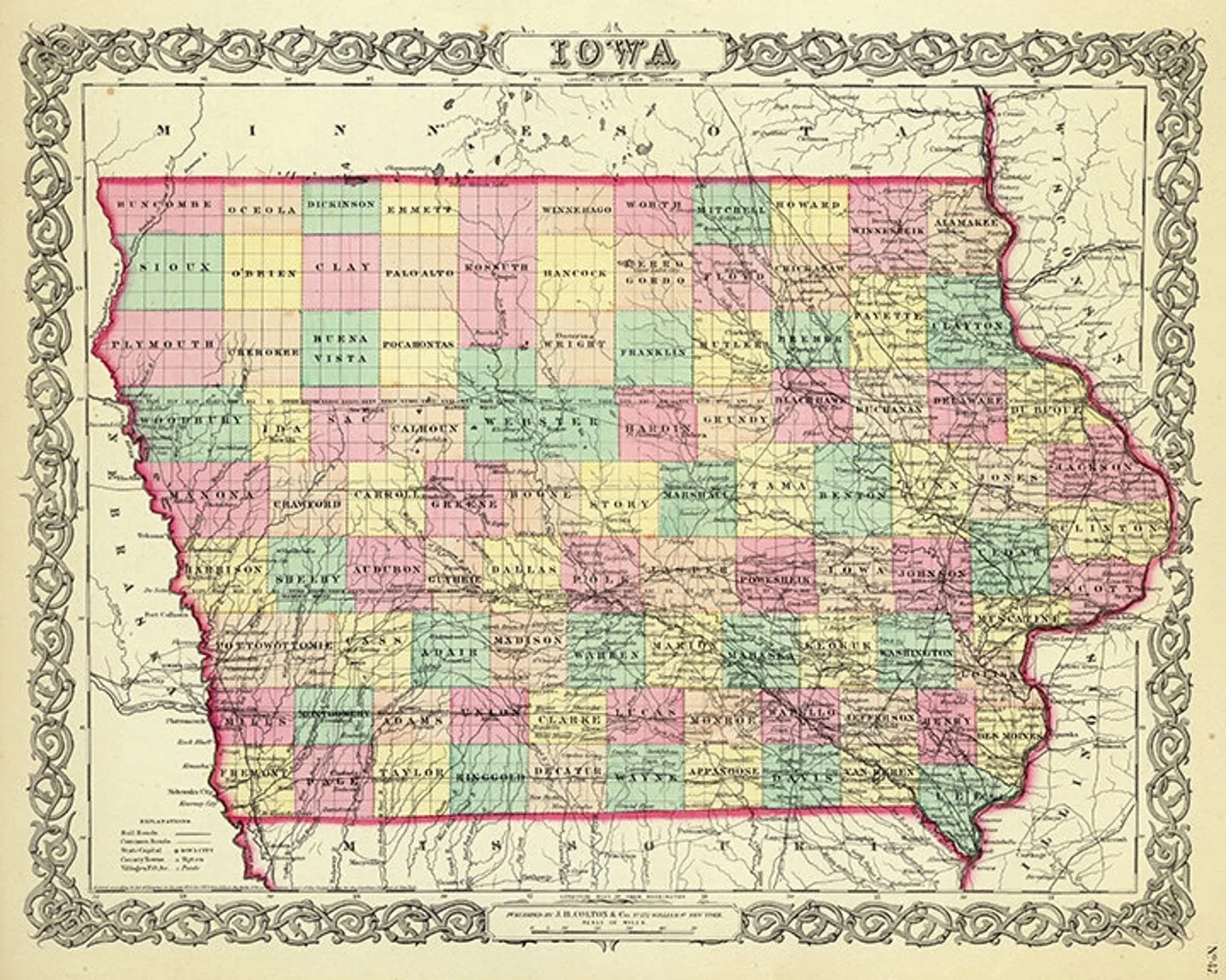

1856 Iowa Map

Preface

In 1941, at the age of eighty-seven, Rosanna (Daman) Bradfield submitted to the Ringgold County Historical Society an essay of her childhood memories of the pioneer life of her parents and siblings. The title of her essay was “Early Dawn in Ringgold County” The historical society published her story in the Ringgold County Bulletin and sold it for 10 cents an issue. [1] Years later, in 2011, The Diagonal Progress newspaper ran a series entitled ”Gone With the Wind” History of Jefferson Township”, which was series of articles written for the most part by pioneers of Jefferson Township of Ringgold County, Iowa. The “Early Dawn in Ringgold County” was published in 5 parts within the “Gone with the Wind” series. [2]

“Early Dawn in Ringgold County: Childhood Memories”

“Written by Rosanna A. Bradfield, daughter of Cyrus B. and Fanny A. Daman, July, 1941, Just as I remember things happening.”

Part 1 [3]

“I have written a little history of Iowa in Ringgold county, Jefferson township. I remember so well the many things that happened in the early sixties. I loved this beautiful country and now I am old and would like to see something printed in your paper that I have written in memory of my childhood days. I could have told many more things that I remembered and could have explained happenings more fully but perhaps my message is too long already, and you won’t want to print it. I could have told you that my oldest sister worked for some people in Mount Ayr by the name of Cyrus Beall in the fall of 1859 in the fall of 1859. That a crippled man by the name of James Westerfield from Mount Ayr taught a three months’ summer school in our district, in a little shanty about 12 X 14. A man from Mount Ayr by the name of John Doze, taught our school. He was a cripple, too. I could tell many things about how the schools were conducted.

I could tell of the strong spring of water that flowed on father’s place. And I have been told that it flows a strong stream yet. Oh, how pure and refreshing the air was then. How beautiful was the rising sun, coming up over father’s timber. What a beautiful picture from childhood memory.

I suppose there will be an Old Settlers Reunion in Mount Ayr this coming July. I would like to be there, but I cannot come. I was eighty-seven years old in March last. My mind is quite clear and I can remember quite clear and I can remember quite clearly many things that took place when I was a child, living in Iowa more than eighty years ago.

I think I can write of things that happened then that might be of interest to some people today. Times have changed much in the past eighty years.

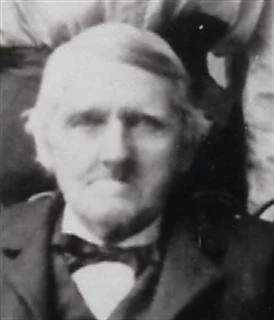

Cyrus B. Daman (1817 - 1914) {4]

My story begins: I am the daughter of Cyrus B. A and Fanny A. Daman. I was born in Marion county, Iowa, March 11, 1854. In the summer of 1858 father sold his farm and was then living on a rented place. But on hearing of good and fertile soil and cheap land of Ringgold county, he with some of the neighbor men desired to go down there and view the land, and if the prospect was pleasing, he would buy land and make a home for his family.”

“The only means of travel he had then, was an ox team and wagon. After corn was laid by, father arranged things at home to make his family comfortable, and prepared for his journey. He with two of three neighbor men made the trip. Father was well pleased with the country and decided to buy, in Jefferson township along the then beautiful stream, West Grand River. He bought eighty acres of farm land along the west of the river, paying five dollars an acre. And bought ten acres of timber land lying along the east side of the river, paying ten dollars and acre. The timber on it was fine. Many large trees of black walnut, shell bark hickory, burr oak, red oak, white ash, hackberry and many other kinds of trees. Man had not touched it with an ax.

A Mr. Hall that had gone with father to look at the country bought land adjoining father’s. And while they were there cut logs and built a small house for him, with the help of some of the settlers there. Father selected a site for him to build on his own land and did some work there. He cut with a scythe and put up two states of fine wild prairie hay. Then made arrangements to rent a house about three miles east of his land for the coming spring, expecting to move his family there until he could build.

In the following spring, 1859, father had been preparing to move down to Ringgold county. Mother, too, had been get ting ready. There were seven children of us. (My next to the oldest sister was married in January.) Father had been load ing things in the wagon to take to our new home and one morning early the wagon was brought near the house and father finished loading it ready to start on our journey.

The wagon was a heavy affair. The wheels were high. The wagon was mostly made of hard wood. People used tar instead of grease to put on the axle to make it run easily, and they had to put it on often. So they kept the tar in sheet iron buckets and tied the bucket to the coupling pole back of the wagon under the wag on bed.

Soon we were ready to start on our journey, after saying good byes to sister and fiends and neighbors, who had come to bid us good wishes and good-byes. Then we started. Father walked and drove the oxen, while my oldest sister, Eunice, and my brothers, Henry and Aurelious, with their good dog drove a small flock of sheep and a few head of cattle in the rear of the wagon.

As it was in the spring of the year, the roads were soft, the wagon it self was heavy and was loaded quite heavily, so it was slow traveling. There were no laid out roads then, but were made where it was the easiest to travel. Therefore they were very crooked. Where there was a steep hill they made the road to go around it, if they could. There were but few bridges but many mud holes. The country was thinly settled all along the way. After we had traveled several miles we came to a lane and passing through it we found several very bad mud holes. There were two heavily loaded wagons that were stuck in the mud, and their teams could not pull them out. The first one had difficulty in pulling through the first mud hole but could not pull through the second one. Father stopped and talked a few minutes with the men, then unhitched his oxen from his wagon and took a heavy log chain out of his wagon and hitched his oxen to the end of the wagon tongue of the first wagon. They had taken rails off the fence and laid them in the mud holes in front of the wheels. Then they made the oxen pull the first wagon out. Then doubled teams and pulled the other wagon out and then pulled father's wag on through. Then they placed the rails they had used on the fence again. After traveling for some time, we came to where there was another bad mud hole along a fence. It looked like some one had had trouble crossing. So father went to take some rails off of the fence there close by when a man came running and hollowing at father to not take any rails off his fence, to just let them along. When he got near enough so father could talk to him, he told father that people would take rails off of his fence and put them in the mud hole and cross over and then leave his rails in the mud and not put them back. Father talked nice to him and told him if he would put them back. He sat on the fence until father used them and crossed over. He thanked the man and put them back on the fence.”

Part 2 [5]

“It was called eighty-four miles from where we started from in Marion County to our new home in Ringgold County. We passed several towns while on the road, but they were small, with no large houses. We traveled until evening and then father stopped where he could get a fenced lot to put his cattle and sheep in and a place for us to eat and sleep for the night. The next morning we had breakfast early and stared on our journey. We arrived at our destination that evening. We were all glad. Father had walked much of the way and the boys were tired, too, walking and driving stock. The first half day was fathers most tiresome for them until the stock got used to following the wagon.

The place where father had rented, the house with a leanto kitchen. I suppose there was about an acre of ground fenced. With some lots fenced for stock. And there were some log buildings for shelter for the stock. Father rented this farm from a man by the name of Montania. A little town had start there called Glen Haven. There was a dry goods and grocery store owned by Mr. John Blake, and he kept the post office there too. Then Mr. Gilles owned a blacksmith shop. Mr. Madison Snider owned a carpenter shop. Mr. Dunlap ran a grist mill to grind meal. Several other families lived in this little town, but I was too young to remember those I was not acquainted with.

After father and mother got settled and had made garden and planted potatoes, father rented some farm land a short distance west of Glen Haven. It was all fenced. He planted it mostly to corn, but planted other crops on it also. What time he wasn’t at work tending his crops, he worked out on his own place hewing out timber to build a house. He had to make several trips to Marion County to get tools and things that he couldn’t bring his first load. He hired some help to build his house, what he couldn’t do alone. He hewed out all of the frame work, but bought the shingles and weather boarding which he hauled from a long distance. He with some help put up a house 16 X 18 feet, story and a half high. He hauled brick and had a nice brick fireplace built.

My mother’s father was an herb doctor. And mother had learned the virtue of many herbs, and was good in nursing and helping the sick. She also as a mid-wife, and had a few calls. She soon made friends in this new neighborhood. Father was a religious man. Honest and friendly and easy to get along with. So we had many friends.

My sister Sarah and I went to school that summer. I was five years old, and this was my first school. A lady by the name of Nancy Tolbert taught the school. (She afterwards married my uncle, Charles Dake.). The school house was made of logs. I presume it was about 14 x 16 feet large. It had been a residence, but the owner had built a frame house, larger and across the road west of this building. And had taken this building for a corn crib. It had been cleaned up a rough floor put in it. It had one window in the north and a door and a window in the south. On the north wall, larger auger holes had been bored and hard wood pins had been driven in the holes for a wide plank to rest on for a shelf for the school children to lay their books when not using them. Also it was used for a writing desk. For seats to sit on, long benches were made of heavy plant wit large auger holds bored in the ends of the plank and hard wood pins driven in for legs. There were not more than four of these long benches, which were set around the room. The boys sat on the east and south of the room and the girls on the west and north. Children from the ages of five to eighteen years old came to school. Not many large boys came for they had to work. Some would come a few days at a time. We sat any where we pleased if we kept on our own side of the room.

We were first taught our ABC’s and had to learn them so that we could point them out anywhere we saw them. Then next we were taught to spell words, and then to put words together. Children under eleven years were not required to take but three studies — spelling, reading and writing. Then we were taught to make figures and to count.

The season was favorable and father’s crops were good. He had his house up and the outside finished all but the doors and window. He has also built corn cribs and other buildings. But he has to make another trip to Marion County before he could finish his house, so that it would do to move his family in.

The town herd of cattle had begun to break into his corn field. Mrs. Blake, the storekeeper, had a large yoke of cattle with long horns and they were the leaders of the herd. They would lift the rails off the fence wit their horns and tear down the fence and let the whole herd into the field. Father had my brothers watch the cattle during the day but the cattle began to break into the field about four o’clock in the morning. But father watched for them and kept them out. Now father wanted to be away from home for a week or so, and went to Mr. Blake and asked him if he wouldn’t keep his oxen up at nights. Father told him why and also told him the boys would watch them during the day time, but they were young boys and it would be hard on thief to watch of nights. He talked nice to father and those him he would kept them up at night. Father told my brothers not to take the dog, Carlo, with them when they went out to watch the cattle. For when the dog got a hold of one, it was hard to make him let go.

The next morning early, the boys went out to the field and there sure enough Mr. Blake had not kept his cattle up as he had promised, and the cattle were in the corn. Mother had fed the dog and the boys had slipped away from him, but two of the neighbor boys, Billie and Nathan Frasier, came to go with my brothers soon after they were gone, and they wanted to take the dog with them, but mother would not let them. But when they got out to the field and saw my brothers trying to get the cattle out of the corn, they said call Carlo. Brother Henry said, “No, Father told us not to take him with us, and wouldn’t like for us to do so.” The boys said, “Mr. Daman didn’t tell us not to take him.” It was a clear, still morning and the Frazier boys began to call “Yah Carlo, yah Carlo,” and like a flash Carlo started. When he got there the Frazier boys set him on the big ring leader ox. And Carlo got hold of his tail and set back and hung on until the tail pulled out. My brothers were scared and sorry. They knew father would not like it. But the Frazier boys just laughed and said it was good enough for old Blake, let him do as he agreed.

The boys watched the cattle out of the corn all that day. Mother had the boys up the next morning at break of day, and the Frasier boys were there by the time my brothers were ready to start. Mother said to the boys, now slip away from Carlo and don’t call him, but when the boys got out to the field some of the cattle were in the corn. The boys were very angry at Mr. Blake and the Frasier boys began their call, “Yah Carlo, yah Carlo.” Yes, Carlo heard and started for the field as fast as he could go. The road to the field ran past Mr. Blake’s store and Mr. Blake was ready with his gun and when Carlo got near, he shot him dead.

Mrs. Gillen came running and said, “Oh, Mrs. Daman, Blake shot Carlo.” Mother went to see if Carlo was dead and Mr. Blake was still holding his gun. It seemed all the town people were against Mr. Blake and felt he had done a mean trick. They told mother that she could have him prosecuted and get judgment, for Carlo was in the public road. Now my mother was not like father. Father would have let it go and would not have any trouble, but not so with mother. She was angry and told Mr. Blake what she thought of him. And when Mr. Gillen proposed to go to Mount Ayr and get an officer and have him arrested, she said go.

While Mr. Gillen was gone, Mr. Blake signed all of his personal property to his brother, but he had eleven lots that he couldn’t dispose of, and at the trial they took the eleven lots for judgement against him. Now Mr. Blake was broken up. His brother wouldn’t return his property, and all the people in town were against him. He and his wife soon moved away and his brother moved his goods to some other town and quit keeping store there. The post office was moved over to Eugene.”

Part 3 [6]

“Soon after father came home he moved his family out to our new home. The doors and windows were not in yet and the floor boards were not nailed down, just boards laid loose were put over head. Father had worked early and late to get our home ready for his family to live in, doing much of the work himself. Mother hung blankets up for doors. Our house faced the west and there were places for a door and a window on each side of the house. Father boarded up the window space that was south of the door.

Now we were at home, how glad we all were. This was a beautiful prairie country. Around about us there were few people that had settled near us. This was a rolling country. As far as we could see north of us the hills were covered with beautiful blue stem grass, now twelve or fourteen inches high, dotted here and there with lovely wild flowers. About a mile and a half west of us three or four families had settled. About a mile and a half west of us a small stream of water ran. Along this stream, there were some timber grew. Wild plum trees, crab apple, red and black haw trees, hazelnut bushes, gooseberry bushes and many other kinds of bushes grew.

Only one family lived in sight of our house, south of us. On the west side of West Grand River, and all the hills were covered with beautiful blue stem grass and prairie flowers, with here and there patches of hazel brush, wild plum, crab apple and red haw trees, also sumac and dog wood and many other kinds of shrubs growing there. Some of these patches were small and some had two or three acres in them, and did not grow far from the river. In the spring these patches became a beautiful sight with their fragrant blooms. Yes this was a wonderful country. The soil was rich, deep and black. It was new.

There was plenty of wild game such as deer, rabbits, squirrels, prairie chickens by the hundreds and many quails. The fur bearing animals were raccoon, otter, mink, weasels, some beavers, muskrats, pole cats and many prairie wolves. There was a bountiful supply of wild fruits that grew in the timber and along the streams, such as plums, crab apples, grapes, strawberries, raspberries, black berries and cherries. These fruits grew to good size and were good tasting. There were no eating insects to harm the fruit and trees then, and the soil was rich and fertile.

Then in the fall there were nuts to gather. In father's timber many large black walnut and shell bark hickory trees grew that bore nice large nuts that we children would gather, what the squirrels didn’t. Then there grew such nice hazelnuts, too. Father and mother worked hard to get along. They had but little to begin with and but little money. Father split rails for seventy-five cents per hundred. He helped around wherever he could find odd jobs to get money to buy material for his house and other necessities.

Our nearest town was Afton, twelve miles northeast of us. There were only three families lived on the road to Afton. It was a small town there, I think it was the county seat of Union county then. Mount Ayr was sixteen miles from our place and was the county seat of Ringgold county. It was larger than Afton, yet it was a small town too, then.

It did not require much those days to start keeping house. People then lived in small houses, not more than two rooms. Most of them were built of logs and most always had a fire place, and they were built of sticks and clay. Most of the floors in the houses were mad of uneven boards, not tongue and grooved, but laid as close as they could get them. Some were nailed down, but some were not. But there were some great cracks between the boards. Father made our first doors of linden lumber and put thumb latches on them to open them with. He also made the window facing of linden boards, too. He only put one window up at first. There were twelve window lights in each window, six lights in each of the lower and upper sashes. We then didn't know anything about window blinds, but mother put up thin muslin curtains to the window. We had never heard of screens to the doors and windows and there were flies by windows and there were flies by the million. When mother went to set the table, one of us children had to stand with a fly brush (or, a limb with leaves on, off of a bush or tree) and keep the flies off the table, that is, in the summer time. No one around there had rugs or carpets on their floors.

Mother’s furniture consisted of a small cook stove, two iron kettles, two iron skillets, an iron dutch oven with an iron lid and an iron tea kettle. A large brass kettle, a tin coffee pot and a tin teapot, a number of milk crocks and tin milk pans, some wood en buckets and a wooden wash tub. All buckets and tubs were made of wood. Mother had three high post bedsteads, and they were high enough to shove the trundle beds under them. There were wooden pins along the bed railing of the bed stead and small rope put around and over these pins lengthwise and crosswise to lay the bed on. They had no mat tresses to make their bed on, but made what they called straw ticks and filled them with straw for their beds. Most people then had feather beds to lay over the straw ticks. Our bedsteads were made of maple wood and not painted. Our chairs were made of hickory wood and the bottoms were woven with hickory bark. They had high backs and were high and were not paint ed either. Her table was not painted either. Her table was home-made. She had but a few dish es. Her knives and forks were steel with wooden handles. They rusted and turned black easily and we scoured them with ashes or brick dust. We churned our butter in a tall stone jar with a wooden lid and dasher. We burned candles. Mother had a candle mold that she could mold six candles at a time. She used tallow and bees wax and candle wick. We were as well fixed as the majority of the families around there and much better than some. Those days they bought all of their groceries by weight. The grocery man bought groceries in the bulk and when the customers bought, it was dipped out and weighed and wrapped up in a very coarse brown paper. No other kind of paper was used. Our coffee came, green kernels. It had to be crowned. Mother put it in the skillet over the fire and someone stirred it all the time until it got nicely browned. Then when wanted to use, we ground it in a coffee mill. Allspice and black pepper came whole and had to be ground. All the sugar we got was brown sugar. When it was bought it was taken out of a barrel, weighed and wrapped in that coarse brown pa per. There was some white sugar made then, called loaf sugar, and it was quite costly. Mother kept it for sick folks. Our matches came in small bundles, wrapped tightly with stiff paper. They were dangerous, when lighted they gave off a gas that would almost strangle a person. In winter sometimes Mother used a long splinter to light the candle with.”

Part 4 [7]

“Mother did all her sewing by hand. She had learned the tailor trade when she was a girl. There were no ready made clothing those days. So mother cut out and made all of our clothing. She made all of father’s and my brothers’ coats, pants, shirts, caps, knit their socks, braided oat straw and made their summer hats. She cut and made pants, coats and vests and caps for others, too.

Mother bought thread to sew with by the pound. It came in skeins and put up In pound bundles. It came in all white in a bundle or mixed all colors. She bought cotton thread to sew light weight goods with but bought linen thread to sew heavier material. I do not remember what she paid for the cotton thread, but paid one dollar a for the linen thread.

Needles must have been scarce with mother, for when she broke the point off of one she gave it to us little girls and we sharpened the point and used it to make our doll clothes with. We pulled the thread out of worn-out clothes, or, we pulled ravelings out of any piece of cloth that was strong enough to use to sew with. Our dolls were rag dolls. We had never seen any other kind, but we enjoyed them as much or more than the children of today do with their costly dolls.

Father sheared the sheep in the spring and mother washed the wool. Then we picked the sticks, burrs and such things that wouldn’t wash out. We picked it nice and clean then father took it to Indianola or Osceola, I forget which, and got it carded in to rolls. Then mother spun it in yarn with her spinning wheel. Then colored it whatever color she wanted - some blue, some black, some red and some green. She spun some yarn fine to make cloth for dresses and skirts, and for father’s and the boys’ shirts and underwear. She spun some yarn to make jeans for father’s add boys’ coats, vests and pants. She bought cotton yarn and colored it for making wrap in making the jeans. then she would send it to someone who had a weaver’s loom.

Mother made her own soap. They saved up hickory wood ashes and put them in an ash hopper and ran water through it and made strong lye and put waste grease in and boiled it until it made soap. Sometimes they took weak lye and made hominy.

As I have said all groceries and dry goods were wrapped in coarse brown paper. We children like to draw pictures but we had but little light paper to draw on. We had our slates. Our parents had writing paper that was called fools cap. But they only kept It to write to friends on. The envelopes were made of deep orange paper and were sealed with little red wafers about the size of a silver ten-cent piece. They came in little round boxes. We children were glad when the last wafer was used for they gave the little boxes to one of us, in our turn, and we valued it very highly, for in those days but very few things came in boxes.

Father had a lead pencil. But none of us children (nor any of the neighbor’s children) owned one. The only kind we has was the kind mother made for us out of lead. She pounded it in the shape of a slate pencil. Then too, father dug a well and we found yellow soap stone. And we found what was known as a keel. We used them to draw with.

After father got his house so his family could winter comfortable in it he chopped wood and hauled a great pile near the house so he could shop it in fire wood at odd times. Then he made rails to fence the ten acres he had broken the sod on. That summer he raised a food crop of corn on the ground he had rented. He had cut with his scythe and put several stacks of prairie hay for his stock that winter. The hay he had cut the fall before had been burned in a prairie fire and he had learned his lesson and had burned a fire guard around his building and where he didn’t want burned.

That winter was cold and there was much snow. Father chopped wood and made rails and worked when he could. Spring came and father with the boys planted the ten acres he had fenced. They sowed four acres of wheat and a nice patch of sorghum cane and a small patch of broom corn. Father had little money but he was industrious and resourceful. He made all of his axe, hoe and pitchfork handles, and made his own garden rakes and all such things. He made their brooms, put hoops on buckets, tubs and barrels when needed. Put bottoms in the chairs and done all that kind of work. In the spring he peeled young hickory for the bark to bottom chairs with. He cut off the outside rough bark, tied the bark in a bundle and laid it up until needed and to dry out. He cut straight hickory wood and split it in lengths and laid it in the dry to use to make handles and things he wanted to make. He cut hickory poles and split them in two and slide them up to dry, to use to hoop barrels and kegs and such things. And when it came bad days, too bad to work out, he worked under shelter and mended such things.

That spring he broke up more prairie and fenced it and planted corn and squashes and pumpkins and all did well. There were so many prairie chickens, quails and birds that they kept the bugs down.

That summer father and Mr. Hall hewed out a cane mill. They hewed it out of maple or hickory wood. Maybe used both in the making. They made two large rollers with cogs and fit them so thighs together that when one turned it turned the other one. It was made very strong.

When the wheat got ripe father cut it with a wheat cradle. The boys raked it in bundles with a wooden rake that father had made and tied in in bundles with straw bands made of wheat straw, and then shocked the bundles. When the wheat got good and dry they were needing flour. Father and the boys cleaned a patch of hard ground and drove the yoked oxen around in a circle on the ground they had cleaned until the ground was quite hard. Then they swept the ground to get all the loose dirt off. They they laid the bundles of wheat around in the circle and drove the cattle around over the wheat until they had tramped the wheat all out of the straw. Then they raked the straw off and raked and swept the wheat and chaff up an put it in grain sacks and took it in grain sacks and tool it to one of the neighbors that had a fanning mill that cleaned the wheat all nice and clean. They would clean six and eight bushels that way. Then maybe the next day father would take it to the mill twelve miles east of East Grand River. A man by the name of Polly owned the mill and it was run by water power. Mr. Polly took toll out of the grain for his pay. Father would go one day and come back the next. Sometimes he had to wait for his grist, for there were others that was there before he was. Then it would be very late when he got home. They ground the wheat into flour, shorts and bran. The shorts then was almost as good as the graham is now. Mother made good pancakes out of the shorts.

The ninth of August a little daughter was born to father and mother. Now there were eight of us children. Five girls and three boys.”

Part 5 [8]

“In September the cane was ripe and ready to make up into sorghum molasses. Father made a long wooden pan of linden boards, about seven feet long and about twenty-six inches deep, and nailed sheet iron on for a bottom. He drove the little nails in thick and let the sheet iron come out farther than the sides and ends of the box. This he made to put the cane juice into boil down to syrup. He dug a trench to put the fire in and made a flue, then landed flat irons over the pit and set his syrup pan over it. They stripped the cane and cut the heads off and left them in the patch, not knowing then that they were good for stock food. Father made a barrel and half of good sorghum, clear and thick.

People did not can fruit or vegetables then. We raised a few small tomatoes, some yellow pear shape, and some were large and rough red ones. We didn’t know they were good to eat only in preserves, and we didn’t know to scald them to get the peeling off. After father made the sorghum, mother made a good supply of tomato preserves. We would take the oxen and wagon out in the timber and gather plums, crab apples and wild grapes, yes, bushels of them and mother made plum, grape and crab apple butter and plum and crab apple preserves with sorghum. She used her large brass kettle to make it in. She boiled them down so thick they would keep good for a long time.

Father made her a drying rack of linden boards. She boiled the ripe plums until they be gan to crack open, then she poured them out on her rack after she had washed it clean. When they got cool enough to handle we washed our hands and took the pits out of them and then she spread them out thinly and spread mosquito netting over them and let them dry in the sun. We picked the grapes off of the stems and spread them on plates and set them out on the rack to dry. Mother dried sweet corn for winter use, too.

Father was needing money. His family and stock were very well supplied with food for the coming winter, as well as he could supply without money. That fall after hauling up wood for the winter and making the home comfortably fixed, he shouldered his ax and walked down to Mount Ayr and chopped stove wood around over the town for the citizens to burn. He would start early Monday morning and come home Saturday evening.

Mother’s brother (Charles W. Dake) lived in Mount Ayr. I do not remember what my Uncle Charley (that is what we called him) was doing then, but afterwards he was the proprietor of a hotel there, for a while. Then after the Civil War broke out, he enlisted and held an office in the army. when peace was declared he came back to Mount Ayr and owned the bank, and was elected county treasurer there. He owned property in the eastern portion of Mount Ayr in 1870. I have heard he had it laid out in town lots and is now called the Dake addition.

I do not know who edited the Ringgold Record then but I do remember father subscribed for it soon after they moved to Ringgold Record thirty-four years ago, saying that my father (Cyrus B. Daman), had made then (the publishers) a call that day and subscribed for the paper. That he has made them a visit once every year for over thirty years, paying for his subscription to the paper.

Father earned money by chopping wood to pay his taxes and to by shoes and boots, for those you needed them, and for some other necessities. Father and the boys worse coarse heavy boots. At night when they took their boots off they used a book-jack. Us children’s shoes were coarse, heavy and unlined, and made on a straight last. Both made just alike no right and left. Our shoe laces were cut from tanned dog hide.

The people held meetings for church services around the neighborhood in their private homes. Although the houses were small, they so arranged it so as the accommodate those that could come. There were no instrumental music, most all sang, and sang soprano, and used small song books without notes. Some did not have books at all but learned from hearing others sing. But all were earnest and sincere. They met at father’s often. He was elder in the church, and when the minister didn’t get there he made good talks. They called the minister, preacher, always, and called there gatherings, meetings. Some of the families had no time pieces. And when there was to be a meeting in the evening, it was given out that there would be a meeting at Brother (wherever it was to be) beginning at early candle light.

That winter the prairie chickens floated there by the hundreds, there where the cane grew, to eat the cane seed that has been left there. Our boys made box traps and set them out there. They caught many. They supplied us with meat, but caught many more that we could eat. When they caught them they would cut their throats and hold them up by their feet until they bled to death, then tied them up by their heads and hung them high (so the wolves wouldn’t get them) north of the house and they would freeze solid. Some times they would have several dozen. Then father would take them to Mount Ayr and sell them for six dollars per dozen.

The winters were cold and much snow fell. The wind had a clear sweep from the north and drifted the snow over objects that it could lodge against. The snow was fine and it packed hard. It piled drifts clear over the stake and the rider fences. We children could take our sleds and run over these drifts. The down was packed and frozen so hard that the horses could run over them and not break through.

As time passed father kept breaking more prairie, and fencing and adding more acres to the farm. This now was his third fall here. He had raised good crops and had shelter and feed for his stock. All stock ran at large then, and fields and yards had to be fenced. They all made rail fences, six rails high, then staked and rider made a lawful fence.

The grass grew so luxuriant that when there came a prairie fire it was something fierce to see, especially when the wind was blowing hard. The flames would travel faster than a horse could run and flames would leap twenty-five or thirty feet high. Father always burned a fire guard as soon as the frost killed the grass so as it would burn. He would plow there or four furrows around his fields, about ten feet from his fence and lots. Then he plowed a few more furrows about two rods away from them, and some still evening he would set fire along the furrows against the wind and burn the grass between where he had plowed. Then he would have a strip more that two rods wide burned around his fields and buildings.

That fall in November, it has been such nice weather, one day father came in the house and said to mother, “Fannie, hadn’t we better get ready to go to Mount Ayr tomorrow? I am afraid this pretty weather isn’t going to last long. And I want to pay the taxes and get some other things before winter sets in, and you want to make Charley, (mother’s brother) a visit and do your trading,”. Early the next morning, father yoked the oxen to the wagon, and put straw in the wagon bed. Mother took that little once’s and they started. It was a beautiful morning in late November. Mount Ayr was a long ways with a yoke of oxen. After a while it began to look stormy in the north and the wind changed and it go of , so cold, and then it got to snowing so hard they could hardly see their way. They got to Uncle Charley’s all right but was worried about us children. When the storm came up, my brothers hurried around and brought in a large supply of wood, hurried out and fed the stock and milked the cows. They were just young boys and it was snowing and blowing very hard, but they finished the chores and it was getting very dark. They brought the big shovel in, the one father used to shovel snow with. The built a big fire in the fire place and all went to bed.

Next morning the storm was over but quite cold. When they opened the door snow fell inside the house. The snow had drifted to the top of the door. The boys had a time shoveling the snow to get to the wood pile and to the stables. The wind has drifted the snow through the cracks into the sheep house and hog house and the chicken house. The boys had to dig the sheep and a few hogs out. The chicken house had been covered with hay but the wind had blown the hay off and the chickens were completely covered up. The boys dug them out and got the snow off of them the best they could, but where to put them they didn’t know. They came and talked to the girls and brother Henry, just a boy, proposed we put them upstairs. We were not using the upstairs then, just loose boards were laid for the floor. We thought that would be all right, so they put them up there and fed and watered them. I think there were two or three dozen of them.

Father and mother were worried about us children, so that morning, early father borrowed a shovel and some more blankets and started for home. He had to shovel out the road in many places to get home. In some places men helped him. They didn’t get home until late that night. They were glad to learn we were all right. The next morning they were awakened by a rooster crowing overhead. It didn’t suite mother. She said, “oh! I can’t stand that.” Father and the boys soon had a place fixed to put them.

Father and mother had to work and economize the first few years that they lived in Ringgold county, but they were industrious and resourceful and as the years rolled on they began to prosper. A saw mill came into the neighborhood and father had lumber sawed and he finished the house. Built a large kitchen and pantry, and other buildings. Bought horses and a lighter wagon. He bought calves from the neighbors and soon had quite a hear of cattle. They did not cost him anything in summer as they ran at large. Now he cut his hay with a mowing machine. He had cows and they raised calves. He raised some cattle to sell. He set out an orchard and a grove and raised grapes and small fruit. He and brother Henry bought more land. Their land ran to the Union county line.

Father loved the home place but when he got old he got hurt and could not stand hard work. And when the railroad went through, and Shannon City was built, they both a home in Shannon City and lived there until mother died in 1906, the father went back to the farm and my brother Charley took care of him until he died in 1914 at the age of ninety-six.

Now how everything has changed. The land has changed. The once beautiful river is just a branch. Most all of the timber is cut off, nothing the same. Anyone wanting to see this beautiful home will fined it south of the county line about two mile west of Shannon City. Just inquire for the Daman old place. My youngest sister, Mrs. G. R. Phillips, lives in Shannon City.”